“The scientist shouldn’t become too adventurous, too competitive. The trouble is, we’re all so human. I’ve never seen a case more governed by human frailties.”

~ Dr. Tony Jones, government pathologist in the Chamberlain trial

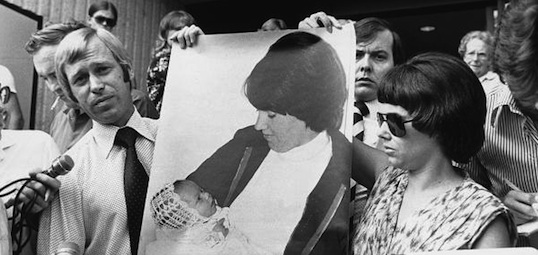

The infamous Lindy Chamberlain “dingo stole my baby” case captivated the nation’s attention. At times it appeared to be a Hollywood circus, a spectacle – the very antithesis of a just legal system. In fact, the case was the inspiration for the 1988 film, “A Cry in the Dark” starring Meryl Streep and Sam Neill. Despite the Hollywood veneer, the facts of the case are incredibly tragic.

In 1980, Ms Chamberlain, her husband and their 3-month-old daughter, Azaria Chamberlain, were vacationing in Ayers Rock when the child disappeared from the couple’s tent. An initial inquest determined that the infant’s cause of death was a likely dingo attack but this finding was quashed in a subsequent inquest wherein Ms Chamberlain was ordered to stand trial for her daughter’s murder.

The Crown’s case was bolstered by the appearance of a number of expert witnesses. In 1983, a jury found Ms Chamberlain guilty of murder. However, the prosecution’s evidence, particularly the expert opinion evidence, subsequently drew significant judicial criticism, particularly from Murphy J who launched a scathing attack on the Crown’s evidence. The Morling Inquiry was established to ascertain what went wrong.

One of the Crown’s expert witnesses, Professor Malcolm Chaikin, the textile expert, gave his opinion at trial that the baby’s jump suit had been cut with scissors rather than shredded by canine teeth. He was characterised as charismatic and a “great performer” who was “so sure [of himself] and eloquent” that he was the one Crown expert whose evidence was virtually unchallenged. Despite his air of self-assuredness at trial, he later acknowledged at the Morling Inquiry that he had given his opinion without having the experimental basis that he would generally expect of first year students.

He admitted that the opinion he gave was not scientifically sound rather it was based on “something I may have felt at the time.” Professor Chaikin’s cavalier testimony had far-reaching implications and undoubtedly contributed to Ms Chamberlain’s wrongful conviction. As Morling J concluded, Chaikin aired erroneous assumptions that were not “based on research work, or any scientific writing.”

Pursuant to section 79 of the Evidence Act 1995 (NSW), expert witnesses are to give their opinions based on their “training, study or experience.” This view is also supported in case law including Dasreef Pty Ltd v Hawchar [2011] HCA 21 wherein the court was clear that an expert must be a person that “has specialised knowledge based on the person’s training, study or experience” and person’s opinion must be “wholly or substantially based on that knowledge.”

The Morling Inquiry also criticised evidence given by pathologist, Professor Cameron. At trial, Professor Cameron gave his opinion that the evidence was not consistent with the dingo hypothesis and he expressed his belief that the baby’s throat must have been cut. It was only at the Morling Inquiry that serious doubt was cast on Professor Cameron’s authority to give evidence on dingo attacks. His past experience was limited to dog attacks and, as Morling J pointed out:

He had no experience of the way in which a dingo or other wild animal would treat a clothed baby as prey and, except for his efforts with the Shroud of he had no experience in ascertaining the cause of death where only blood stained clothing of the deceased is available.

Furthermore, in his submission to the coroner, Phillip RC QC criticised the speculative nature of Professor Cameron’s evidence stating that the experiential basis for his claims had about as much foundation as that for a vision of “Father Christmas in the clouds.” Again, this illustrates how imperative it is that expert witness evidence is grounded in the expert’s substantive experience and/or credentials. Where this threshold requirement is not satisfied, there can be detrimental consequences for affected parties and it is also injurious to the legal profession as a whole.

The Lindy Chamberlain case was an enthralling, albeit very serious case that generated national and international interest. Indeed, the “dingo stole my baby” case became salacious media fodder, masking the serious issues at the heart of matter. Indeed, Ms Chamberlain’s plight represents one of Australia’s gravest miscarriages of justice. Many lessons can be drawn from this tragic experience. The flawed testimonies of Professors Cameron and Chaikin illuminates the need to ensure that expert witness opinion is grounded on something tangential – namely the witnesses’ experience, training or study.